Connecting the Dots: How a 40-Year-Old Interface became the Future of AI

In 1964, Robert Moog demonstrated something revolutionary: a wall of knobs, switches, and dangling cables that could produce sounds no one had heard before. Musicians didn’t need to understand electronics. They needed to understand connections – plug this oscillator into that filter, route the output through an envelope, and listen to what emerges.

Sixty years later, we’re building AI systems the same way.

The node-based interface – boxes connected by lines, data flowing visibly from input to output – has quietly become one of the most successful interaction paradigms in computing. From music studios to children’s classrooms to enterprise automation, these visual programming environments share a common insight: humans think in connections.

Now, as AI systems grow more complex and more consequential, the node graph is having its biggest moment yet. This isn’t coincidence. It’s convergence.

The Physical Origins:

We’ve Always Thought in Connections

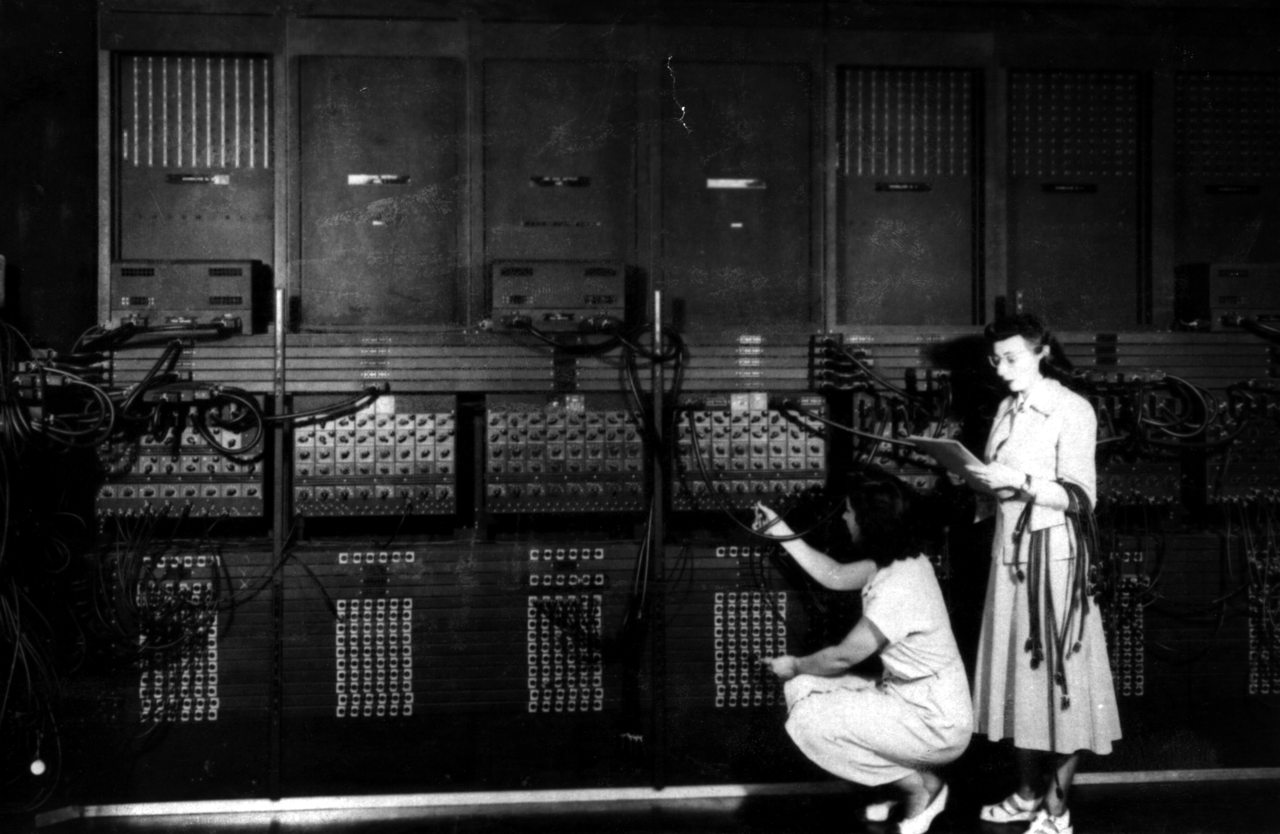

Before software existed, programmers worked with their hands.

ENIAC operators in the 1940s configured the machine by physically rewiring patch panels – moving cables to route data through different processing units. Telephone switchboard operators connected callers by plugging cables into jacks. Recording engineers routed audio through mixing consoles, patching signals through compressors and equalizers.

These weren’t programming environments in the modern sense. But they established something profound: the mental model of things connected to other things as the fundamental unit of complex systems.

The modular synthesizer made this metaphor musical. When Wendy Carlos used a Moog to record Switched-On Bach in 1968, she wasn’t writing code – she was designing signal flow. Sound originated at oscillators, passed through filters, was shaped by envelopes, and emerged transformed. Every patch cable was a decision made visible.

This physicality mattered. You could see the logic. You could trace a sound from source to speaker by following wires with your eyes. Debugging meant finding the loose connection.

The Digital Translation: Miller Puckette’s Gift

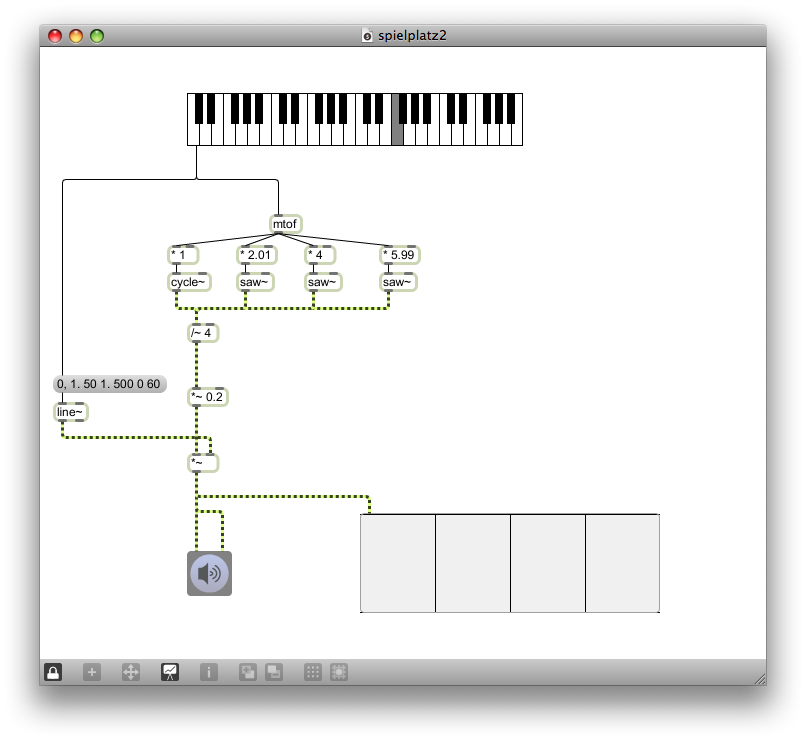

In 1985, a researcher at IRCAM in Paris named Miller Puckette faced a problem. Composers wanted to create interactive computer music, but writing C code was a barrier. The solution wasn’t to make programming easier – it was to make it visual.

Puckette created Max (named after computer music pioneer Max Mathews), a graphical environment where composers could build audio systems by connecting boxes with virtual patch cords. The interface mirrored what musicians already knew from synthesizers. Instead of writing:

output = filter(oscillator(440), cutoff=1000);They could draw it:

[oscillator 440] → [filter 1000] → [output]

Max evolved. IRCAM released Max/FTS for real-time audio processing. Puckette later created Pure Data as an open-source alternative. David Zicarelli founded Cycling ‘74 to develop Max commercially, adding MSP for audio synthesis and Jitter for video.

But the core insight remained unchanged: the best abstractions don’t hide complexity – they make it navigable.

A Max patch for a sophisticated audio effect might contain hundreds of objects. Yet you could still trace any signal from input to output. You could isolate sections, test components, and understand the whole by understanding its parts.

This wasn’t dumbed-down programming. Professional composers, sound designers, and installation artists used Max to create work that would be nearly impossible to write as text. The visual representation wasn’t a crutch – it was a different cognitive mode.

The Democratization Wave:

From Studios to Classrooms to Boardrooms

By the 2000s, the node-based paradigm was spreading far beyond music.

Teaching Children to Think Computationally

In 2007, MIT released Scratch, a block-based visual programming language for children. Instead of typing syntax, kids snapped together colorful blocks like LEGO pieces. The blocks had shapes that only fit together in valid ways – loops contained other blocks, conditions had boolean-shaped slots.

Scratch proved something important: visual programming wasn’t just for specialists. Millions of children who had never written a line of code were creating games, animations, and interactive stories. They were learning computational thinking – loops, conditionals, variables, events – without getting stuck on semicolons.

The insight extended to robotics (Minibloq, CodeSnaps), educational games (Lightbot, Kodu), and transitional environments like Pencil Code that let learners move from blocks to text.

Engineering Goes Visual

Meanwhile, engineers discovered that node-based interfaces could handle serious work.

National Instruments’ LabVIEW brought graphical programming to test automation, data acquisition, and instrument control. Scientists and engineers who weren’t professional programmers could build sophisticated measurement systems by connecting function blocks.

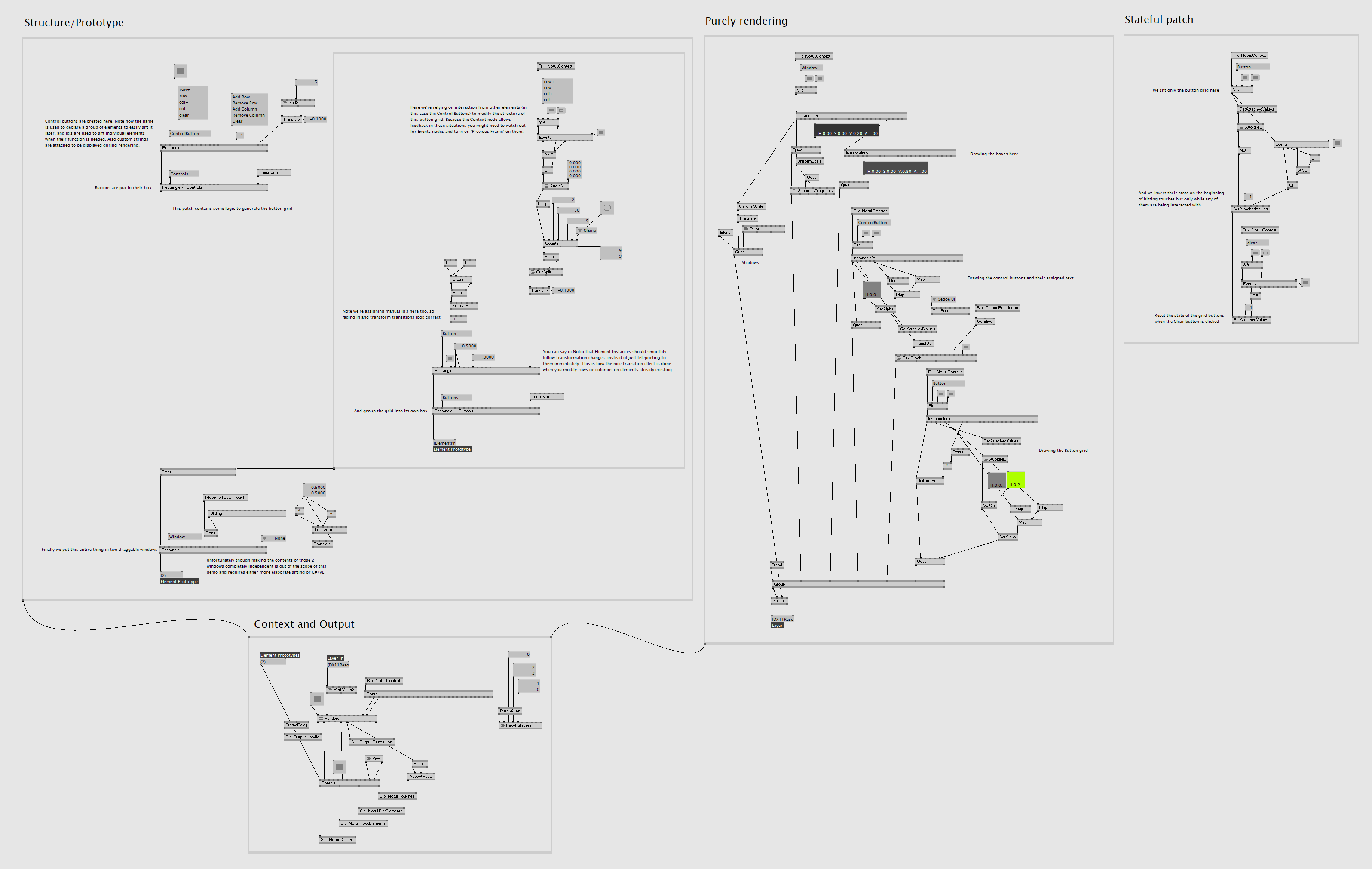

In the world of real-time visuals, vvvv emerged from Frankfurt-based media studio MESO. Developed internally from 1998 and publicly released in 2002, vvvv was built for rapid prototyping of large-scale media installations – think reactive video walls, generative graphics, and immersive experiences. Where Max/MSP focused on audio, vvvv embraced real-time video synthesis and motion graphics, leveraging the emerging power of gaming graphics cards. Its “patch while running” approach – modifying programs live without restarts – became essential for artists working on installations where downtime meant dark screens.

The game industry followed. Unreal Engine introduced Blueprints, a visual scripting system that let designers build complex gameplay logic without writing C++. A designer could create an enemy AI behavior, a puzzle mechanic, or a cinematic sequence by connecting nodes – and a programmer could later optimize the hot paths in code.

This challenged the assumption that visual programming was only for beginners. Professional game developers were shipping AAA titles with significant Blueprint content.

Business Automation Without Code

The third expansion was perhaps the most consequential: business users discovered they could automate their own workflows.

Zapier, Make (formerly Integromat), and Microsoft Power Automate let non-developers connect SaaS applications visually. “When a form is submitted, create a row in the spreadsheet, send a Slack message, and add a task to Asana” – expressed not as code, but as a diagram.

Node-RED, created by IBM in 2013, brought the same paradigm to IoT and backend services. Hardware devices, APIs, and data transformations could be wired together in a browser-based flow editor.

The pattern was clear. Whenever a domain involved modular components that needed to be composed and configured by people who thought in terms of flow, node-based interfaces emerged.

Which brings us to AI.

The AI Moment:

The Interface These Workflows Were Waiting For

Large language models are remarkable. They’re also opaque, unpredictable, and difficult to integrate into reliable systems.

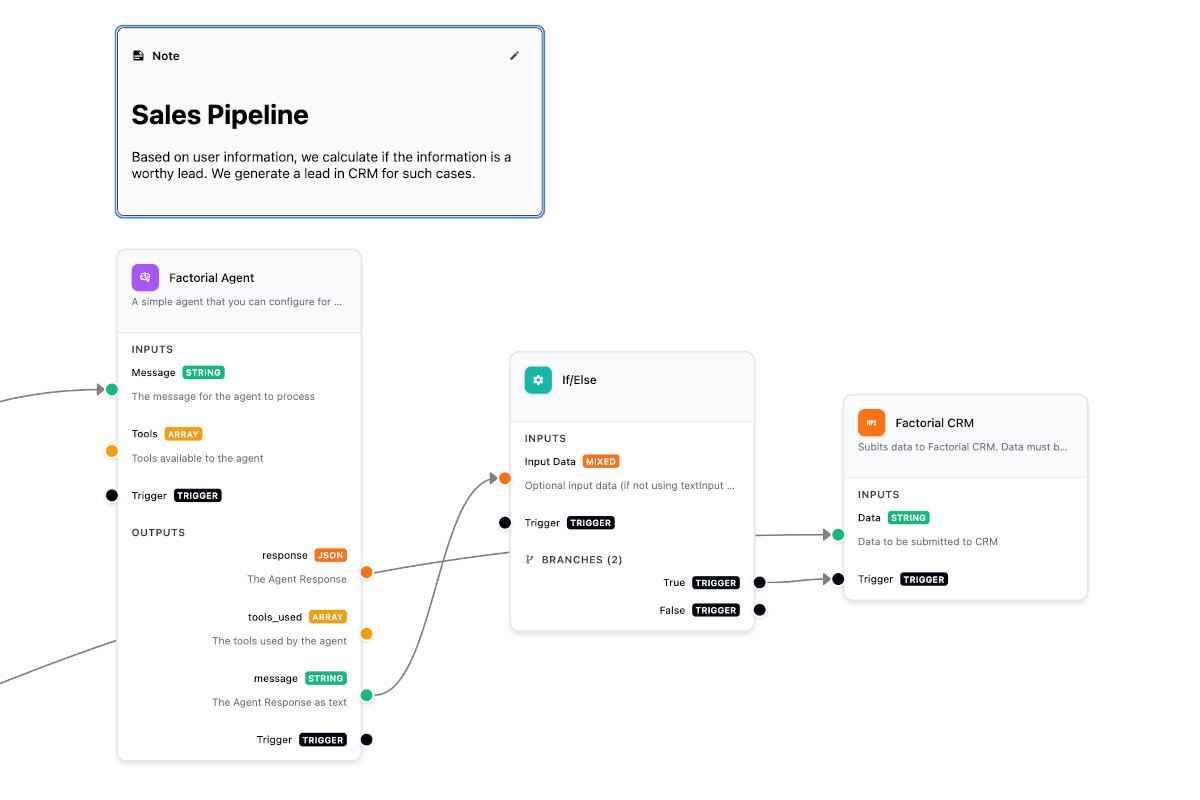

Building production AI isn’t about calling an API and hoping for the best. It’s about orchestrating components – retrievers, prompts, tools, memory, guardrails – into systems that actually work. This is exactly the problem node-based interfaces were designed to solve.

Modularity Meets the Digital Ecosystem

An AI application isn’t a single model – it’s an assembly of embedding models, vector stores, language models, and crucially, connections to the outside world. The real power emerges when AI agents reach beyond their context window to interact with external systems: databases, calendars, email, file storage, web APIs, enterprise software.

A node graph shows this architecture directly. You can see that your system uses OpenAI embeddings, queries a Pinecone index, routes through Claude for generation, and connects to Salesforce for CRM data and Slack for notifications – all in one glance. Each external service becomes a node, each API connection a visible edge. The AI doesn’t exist in isolation; it exists as part of a larger digital ecosystem, and the graph makes those relationships explicit.

This visibility matters most when things go wrong. Why did the model hallucinate? What context was retrieved? Which tool was invoked, and what did it return? In text-based code, these questions require logging, debugging, and mental reconstruction. In a node graph, you click any connection and inspect the data that flowed through it. When your AI agent sends an unexpected email or updates the wrong record, you can trace the exact path from input to action.

Signal Processing for the Age of AI

A synthesizer patch routes audio through filters and effects. An AI workflow routes context through prompts and models. The metaphor maps surprisingly well.

Consider what happens in a RAG pipeline: a user query enters, gets embedded and matched against documents, the retrieved context is formatted and inserted into a prompt template, the prompt goes to a model, and the response passes through validation before returning. Each step transforms data. Each connection carries meaning. System prompts, few-shot examples, output parsers – these are all “effects” that shape how information flows from input to output.

But unlike audio processing, AI workflows rarely run in straight lines. They branch when the model is uncertain. They loop until output passes validation. They fan out to search multiple sources in parallel, then merge results. Text-based code obscures these patterns in conditionals and callbacks. Node graphs reveal them – you see the branch, follow both paths, understand where they reconverge.

Humans as Nodes

Trustworthy AI often requires human oversight. A fully autonomous agent might be powerful, but a system that pauses for approval at critical points is reliable.

Node-based interfaces make this natural. An approval node sits between the AI’s decision and its execution, as first-class as any model or tool. A feedback connection lets human guidance flow back into the system. The workflow explicitly shows where humans intervene – reviewing content before it’s published, approving actions before they hit production systems, providing course correction when the model drifts.

Composition Creates Emergence

The magic of node-based systems has always been this: simple components, connected thoughtfully, produce complex behavior.

A single oscillator is boring. Route it through a filter controlled by an LFO, add feedback, mix with a delayed copy of itself – suddenly you have something alive. AI agents work the same way. An LLM alone is limited. Connect it to retrieval, give it tools that reach into your CRM and calendar and codebase, add memory that persists across sessions, create feedback loops that refine outputs – and capabilities emerge that none of the components had individually.

The node graph doesn’t just represent this composition. It invites it. What if I add a node here? What if I route this output to a different service? The friction of trying new configurations is nearly zero.

The Convergence:

AI as the Universal Connector

We’ve come full circle.

In 1964, patch cables connected sound modules. In 2024, node graphs connect AI capabilities.

And now something fascinating is happening: AI itself is becoming a node.

Protocols like MCP (Model Context Protocol) let AI agents plug into any service – calendars, databases, APIs, file systems. The model doesn’t just process data; it navigates a graph of available tools.

The node graph isn’t just how we build AI workflows. It’s increasingly how AI perceives the world – as a network of capabilities that can be composed, routed, and orchestrated.

Miller Puckette couldn’t have known, when he drew the first Max patch in 1985, that he was designing the interface for systems that didn’t exist yet. But he understood something fundamental: when you’re working with modular systems, thinking in connections isn’t a limitation.

It’s a superpower.

Where We’re Heading

The tools are already here. LangGraph, Flowise, n8n, Rivet, and dozens of others offer node-based interfaces for AI orchestration. Enterprise platforms like Make and Zapier are adding AI nodes alongside their traditional integrations.

But we’re still early. The current generation of AI workflow tools often feel like Max did in 1988 – powerful for experts, but not yet refined for everyone.

What comes next?

- Better debugging: Click any edge, see exactly what data flowed through, understand why the model made its choice

- Version control for workflows: Diff and merge visual graphs as easily as code

- Collaborative editing: Multiple people building the same workflow in real-time

- Hybrid interfaces: Seamlessly move between visual graphs and text code, each representing the same system

- AI-assisted workflow design: Models that suggest connections, identify bottlenecks, and optimize configurations

The forty-year journey from patch cables to prompts has been about finding the right abstraction for complex systems. Node-based interfaces aren’t the answer to everything – but for modular, flow-oriented, inspection-dependent work, they’re unmatched.

AI workflows are all of those things. The interface was waiting. The moment has arrived.

Building Our Own Dots: Introducing FlowDrop

This isn’t just a history lesson for us – it’s a blueprint.

At Factorial, we’ve been building FlowDrop, an open-source visual workflow editor designed for exactly this moment. The project was created by Shibin Das and developed by our team as a pure UI component that lets you build beautiful workflow editors in minutes, not months. Built with Svelte 5 and @xyflow/svelte, FlowDrop carries forward the same philosophy that made Max and Pure Data so powerful: give people the right visual primitives and get out of their way.

The philosophy is simple: you own everything.

Most workflow tools are SaaS platforms that lock you in. Your data lives on their servers. Your execution logic runs in their cloud. You pay per workflow, per user, per run.

FlowDrop is different. It’s a visual editor – nothing more, nothing less. You implement the backend. You control the orchestration. Your workflows run on your infrastructure, with your security policies, at your scale. No vendor lock-in. No data leaving your walls.

It ships with seven purpose-built node types – from simple triggers to complex gateway logic – and integrates with any backend. For Drupal shops, we’ve built a companion module that provides AI integration, data processing, and automated job execution out of the box. But FlowDrop works just as well with Laravel, FastAPI, or whatever you’re already running. Five lines of code gets you a fully functional workflow editor:

<script lang="ts"> import { WorkflowEditor } from '@d34dman/flowdrop'; import '@d34dman/flowdrop/styles/base.css';</script>

<WorkflowEditor />We built FlowDrop because we believe the forty-year journey from patch cables to AI orchestration deserves tooling that respects both the paradigm’s elegance and your ownership of your systems.

The dots are there. FlowDrop helps you connect them.

Check out FlowDrop on GitHub →

Thanks to Miller Puckette for inventing the paradigm, to Scratch for proving children could use it, and to everyone building the next generation of visual AI tools.

Further Reading

- FlowDrop: Open-source visual workflow editor

- FlowDrop for Drupal: Backend integration module

- Future of Coding Podcast: Max/MSP and Pure Data with Miller Puckette

- Cycling ‘74: Max/MSP

- Pure Data Community

- Node-RED

- Scratch

Want to know more? Reach out to me or Shibin, we’re happy to help!